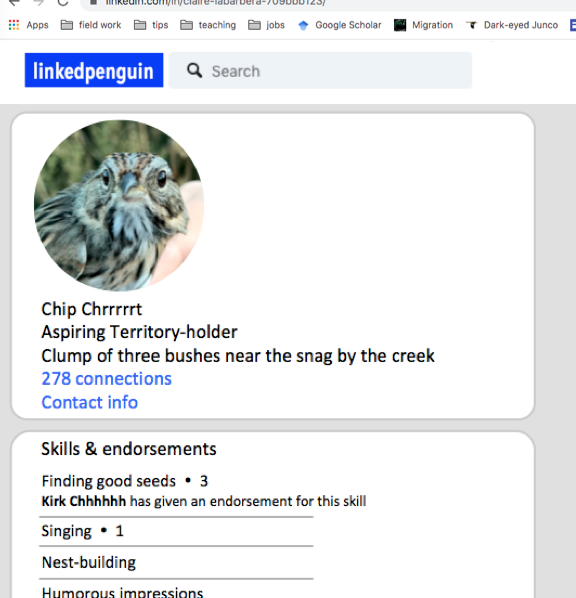

Facebird. Instagrebe. Tikstork. Linkedpenguin. Twitter. Only one of these is real, and I’m pretty sure that even on Twitter the number of actual birds participating is negligible. Birds do have social networks though—the old-fashioned analog kind, made up of flockmates and siblings and reproductive partners and rivals. Some species, like the Black-capped Chickadee, have tight-knit flocks with elaborate social hierarchies; others, like the Hermit Thrush, live most of their lives alone. These differences are surely fundamental to shaping the lives of birds, from their mundane daily experiences to how they tackle life-or-death challenges. If you spot a deadly predator like a Cooper’s Hawk, do you try to disappear quietly into the brush or do you risk your safety by giving an alarm call to warn your companions?

Continue reading