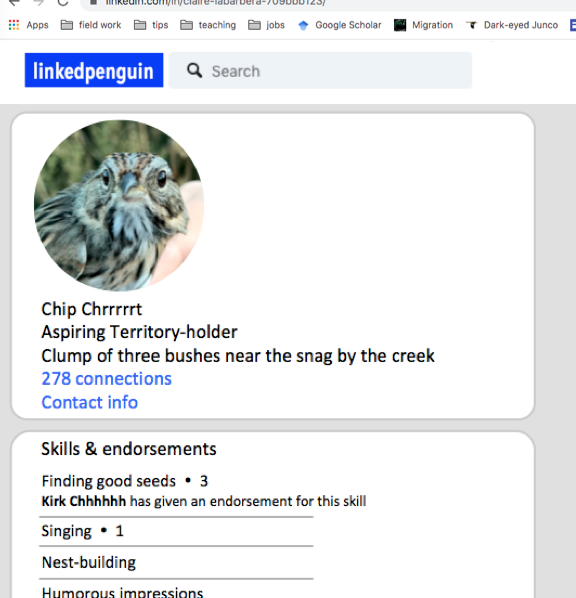

To identify the species, sex, and age of a bird, a bird bander in North America relies either on personal experience with the species or on the massive handbook of bird descriptions known as the Pyle Guide. The Pyle Guide is full of confidence-instilling descriptions like “Juvenile rectrices usually pointed, but occasionally truncate” and “Male scapulars brownish-black, compared to blackish-brown in female.” To make matters still more confusing, birds can vary from site to site, meaning that the description in Pyle based on a population 100 miles distant may not be correct for your own local population. One of the best tools a bird bander can have, as they squint at a bird and wonder whether its iris is “red-brown” or “maroon” and whether that is even relevant to their local birds, is a comparison photo showing local birds.

You have to be a bit lucky to capture such photos: you have to happen to catch both birds at the same time. When you usually catch five or fewer birds at a time, as we do, the chances that any two of them will be an informative comparison becomes small. Each of these pair photos is a little special for this reason.

Continue reading