It’s the time of year when migrants come through the banding station on their way from their breeding grounds in the north to their wintering grounds in the south. We see a greater variety of species now—not just those who like to breed here, but everyone who thinks our patch of forest looks like a good place to stop for a snack. It isn’t just that these are different species, though: these birds have a different feel to them. These are travelers on a genuinely long and perilous journey. We banders are, I hope, just a blip in any bird’s day—a frightening moment to be shaken off by mid-afternoon—but the days we interrupt for these migrating birds are epic days.

This is physically manifested, on the birds, as fat.

A small bird with a fast metabolism is never more than a few bad days from starvation, particularly when undertaking the energy expenditure of flying across a continent (or two). Healthy fat reserves are essential. Before migrating, birds go into hyperphagia (literally “overeating”), increasing their food consumption by 25-30%. Some songbirds can nearly double their weight prior to migration.

We see this fat on the birds that come through the banding station. Bird skin is so thin that you can see right through it to the muscle, bone, or fat beneath: muscle is deep red, bone is white, and fat is pinkish-yellow. Unlike humans, birds don’t deposit fat in even layers under the skin over their entire body; rather, there a few discrete locations where the fat is stored.

A very thin bird may have no fat visible at all. When you blow its breast feathers out of the way with a gentle breath, you will see the red of the large flight muscles topped by a deep depression, out of which emerges the long, thin neck. This depression—the furculum—is outlined on two sides by the wishbone; if you ever tried to stuff the wrong hole in a Thanksgiving turkey, this was that hole.

The furculum is right under the bottom of the black “beard” on this very handsome, very angry Bullock’s Oriole.

The furculum is the first place a bird puts fat. First a thin yellow line of fat appears at the deepest trough of the depression; as the bird puts on weight, the line expands into a layer of fat, thicker and thicker until there is no depression at all, just a smooth triangle of yellow between the breast and the neck.

As the furculum fills up, the bird will start to put fat in its two other available storage spots: on its abdomen, between the bottom of its ribs and its tail; and in its wingpits (i.e. armpits, but for wings). A really well-fatted bird will have yellow patches of fat in the furculum, abdomen, and under both wings. We only see birds this fat during fall migration.

This migrating Wilson’s Warbler, caught a few weeks ago, was very fat.

This fat is, to me, like looking at someone’s emergency preparedness kit and seeing all kinds of extreme medical equipment—tourniquets and burn bandages and bone saws—or like finding out that someone has taken out twenty different kinds of expensive insurance: the fat says, “I expect things to be tough, and I am as ready as I can be.”

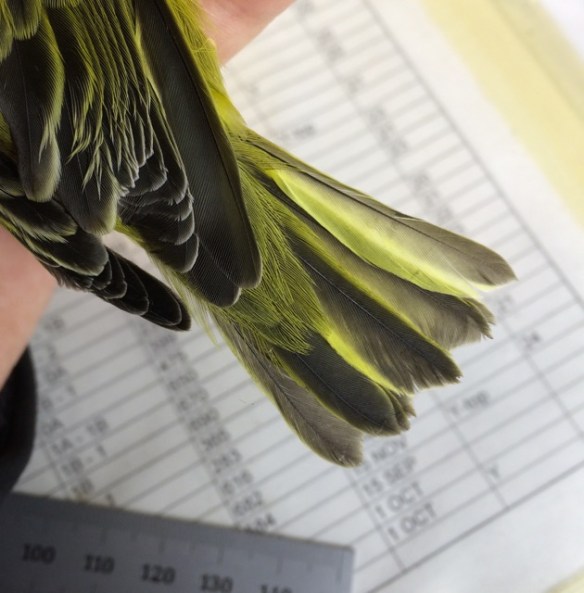

Migrating Yellow Warbler.

Finding these glimpses into life-and-death drama in these tiny, fluffy, adorable packages is one of the things I love about birds.

Most of our migrants so far have been Wilson’s Warblers and Yellow Warblers. The Yellow Warblers delight me for two reasons: they were the first warbler I learned to identify, back when I was just starting to bird; and they are sneaky, always trying to convince you that they are something else—an Orange-crowned Warbler, say, or a Common Yellowthroat.

Yellow Warbler

Common Yellowthroat (note the faintest shadow of that characteristic black mask, just starting to appear).

For some reason our Yellow Warblers, unlike the ones I first learned on the east coast, never seem to have any of their characteristic red breast streaks. As I said: sneaky.

Fortunately we still have another characteristic marking by which to know them: the yellow on the tailfeathers.

Also they are just *so* yellow.

I think this one is trying to look like a mouse. Look at those whiskers!

This season brings us non-avian sights too. The dragonflies are more active than ever, and periodically have to be disentangled from our nets.

A blue dasher sits on my fingers for a moment after being extracted from the net.

A common green darner, angrily chewing on the net.

While furling and tying the nets recently I found a strange thing on one of our net-tying ropes:

Katydid eggs! They will hatch too late to feed this season’s migrant birds, which I imagine the katydids are perfectly happy about.

More than anything, the migrating birds remind me what a small slice of life I am privy to. They fly from Alaska to Mexico under their own power, sleeping in unfamiliar trees and braving unexpected storms, and all I can do is note the fat in their furculum.

Thank you for this informative post, and for the great pictures (and for the “tips” on identifying a yellow warbler).