In the field, I become especially attentive to temperature. Is it too cold to catch birds? Are my hands warm enough to not chill a bird when I hold it? Recently, a friend very kindly let me take his FLIR ONE to the field: this is a device that fits over your phone and lets you take photos of heat. (Normal photos are of visible light.) Warmer objects show up as yellows and whites; colder objects are blue and black. The photos it takes aren’t of absolute temperature—that is, 40 degrees F isn’t always the exact same color—but rather of relative temperature: within the same photo, you can use the colors to compare temperatures, but you can’t compare across photos.

This was a lot of fun to use in the field, especially since the weather so generously gave us lots of temperatures to observe by snowing on us. Did you know that snow is cold, and humans are warmer than snow?

We had several opportunities to observe the coldness of snow.

In a rather eerie effect, the coldness of snow makes trees appear warm.

When the air is cold, the river is warm.

A mushroom is colder than the ground.

Animals are warm. In the chilly morning air, a Steller’s Jay is a blazing spot of heat.

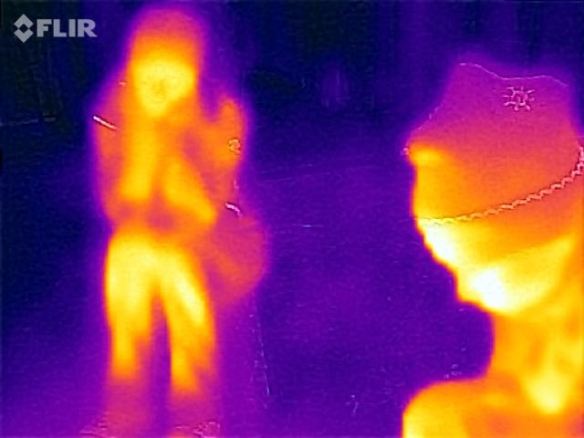

Humans are also warm, and we use tricks to stay that way.

And what about… fire?

Back home, my cat decided to help me refold my tent.

Not surprisingly, she is hot too.

And her heat-ghost lingers even after she leaves!

Many thanks to Taylor for letting me borrow his FLIR ONE!

Those are great. The marshmallow is my favourite. I may have to check into this device.

Fascinating

Nice, what a fun toy.

(I hate to be *that birder* but it’s StellEr’s jay, not StellAr’s…)

Aah, I’m mortified – I never noticed that! I’ve been spelling it with an A for years! Thanks for pointing this out!

Hi, random stranger here. I’ve always wondered something and am hoping maybe your recent experience might lend some insight! In short, would FLIR be useful for nest searching?

I used to be part of a nest searching crew on the Trinity River in northern California. Early in the season, morning temps could be upper 30s-low 40s. We’d be freezing our butts off looking for YBCH nests in chest-high Himalayan Blackberry. I could just picture momma Chat sleeping fluffy and warm on her toasty eggs. The problem was, Chat nests are so well camouflaged your face could be 9″ from them and you’d never see it through the leaves. Even though you KNOW it’s right there! (Or maybe a foot to the left, or the right… or maybe behind you?)

I always thought FLIR technology could be used to find nests on the cold mornings – or at least the surface-level nests. Though some argued birds were too well camouflaged to contrast against the chilly air, I think your post proved otherwise. And even if momma Chat flushed, her eggs would be 3-5 tiny lighthouse beacons guiding you to the nest.

What do you think? Would the technology be sensitive enough to detect surface-level nests amidst the leaves, at least on the colder mornings? I’m still dying to try this. Maybe you could do a little FLIR nest-finding recon for us!

Thanks for humoring a random stranger. I always enjoy your writing.

I thought about this a lot too. I think it would only work with nests that are camouflaged but fully visible – the FLIR can’t see through obstacles, so if the nest was hidden behind leaves/grass/whatever, you wouldn’t see it. (It’s hard to see that in these photos, since I selected the best photos, not the ones where the animal was hidden behind something.) It would work well with, say, nighthawk nests or some shorebird nests: nests where the eggs (or mom) are right there in the open, but so well-camouflaged that our eyes miss them. Or if the nest/mom was *partially* visible, but the outline was broken up by branches so that your eyes didn’t recognize them – which might be the case with some of the chat nests?

It’s certainly a beguiling concept, isn’t it: something that would let you see through all the brush right to the nests! I wish I had a more positive answer :-)