More than fifty years ago, Russian scientists began an experiment in domestication. At that time, silver foxes had been raised for fur for about 100 years already, so their care and breeding was well known. The scientists began their project like this: they would approach the cage of a silver fox and note its response. The fox would crouch, ears flattened, snarling in fear, or else back away as far as it could until its body was vertical against the back wall of the cage. All of the foxes were frightened of the humans—but some less than others. The scientists chose the foxes that showed the least fear of humans, and bred them. Then they did the same with the pups, raising up and breeding the least-frightened of them; and so on and so on.

The original foxes were as close to wild animals as anything can be after being bred for fur for a century. Their descendants, after many generations of selection for just one thing—tameness, a liking of humans—look and act like dogs. They seek out humans, they whine and lick your face, they wag their tails. They even look like dogs—mostly, like border collies.

Of course, selective breeding by itself isn’t (generally) very difficult. You could make a fox that looked like a border collie by searching for abnormally-pigmented foxes and breeding them until you got what you wanted. But this study didn’t do that: they bred only for tameness. All sorts of other traits showed up in the tame pups not on purpose, but because of the genetics of the animals.

The friendly foxes had white markings on their faces. Some of them had tails that curled upward; some had floppy ears. Some of them had strange body shapes: stubby legs, shorter snouts or longer skulls, underbites and overbites, widened skulls. They acted like curious, eager pups for longer, and made some pup noises even when they were adults. Some of them could understand a human’s pointed finger—which baby humans can do, and dogs can do, but chimpanzees cannot.

Basically, all of their changes made them more and more like dogs.

Greyhound: elongated skull.

Image courtesy of PG Palmer (www.pgpalmer.net), as licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 Generic.

It makes a certain amount of sense that domesticating foxes might have similar effects to domesticating wolves: foxes and wolves are fairly closely related, so if human-loving is somehow related to curly tails and floppy ears and face licking in one, it’s not astonishing that you see the same in the other.

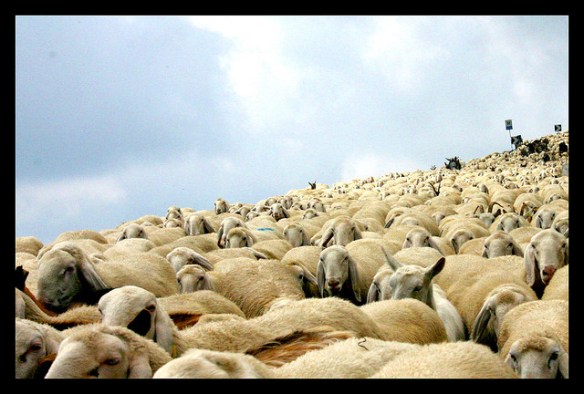

But it isn’t just dogs: when you start to think about it, many of these traits show up in lots of domesticated animals. Those white markings, for instance:

And the floppy ears:

So why does selecting for tameness lead to all these other changes? Well, we don’t know. There are many possible reasons, and researchers are only beginning to explore them. But the fox domestication experiment has far-reaching implications: it suggests that changes in one trait can sweep along changes in many other, apparently-unrelated traits in unexpected ways; it suggests that changes in behavior—for “liking humans” is a behavior—can bring about changes in form as well.

And it suggests that when your dog gives you that look that says, “I love you with every fiber of my being, human food source!” he isn’t lying: just about everything about him has been shaped so that he can love you.

References:

Trut L. 1999. Early canid domestication: the farm-fox experiment: foxes bred for tamability in a 40-year experiment exhibit remarkable transformations that suggest an interplay between behavioral genetics and development. American Scientist 87(2):160-169.

Trut L, Oskina I, Kharlamova A. 2009. Animal evolution during domestication: the domesticated fox as a model. BioEssays 31:349-360.

*Photos obtained from Flickr and used via Creative Commons. Many thanks to these photographers for using Creative Commons!

AS always, fascinating.

I had seen a television programme on this theme, also taking place in Russia, but with wolves not foxes.

My spouse and I absolutely love your blog and find a lot of

your post’s to be precisely what I’m looking for.

Would you offer guest writers to write content in your case?

I wouldn’t mind producing a post or elaborating on a number of the subjects you write with regards to here.

Again, awesome blog!

Book on this now available: ” How to Tame a Fox (and Build a Dog): Visionary Scientists and a Siberian Tale of Jump-Started Evolution” by Lee Alan Dugatkin and Lyudmila Trut, (University of Chicago Press)